Article: Ayin Es Describes Amy Sillman

Ayin Es Describes Amy Sillman

Multimedia artist, writer, and musician Ayin Es was born in Santa Monica, CA, and identifies as trans/nonbinary and genderqueer.

They are known for their unusual oil paintings, drawings, collages, and Artist's books. A two-time recipient of ARC Grants from the Durfee Foundation, they also won a Pollock-Krasner Fellowship, the Wynn Newhouse Award, the Bruce Geller Memorial Award from the American Jewish University, and an Artist Achievement Award from the National Arts & Disability Center/UCLA. Widely collected, Their works reside in many predominant collections and museums such as the Getty, Brooklyn Museum, and National Museum of Women in the Arts, to name a few. Learning music at an early age, Ayin studied drums with prestigious teachers and played professionally for over fifteen years. They have toured the US and Canada, recorded and worked with notable musicians and producers, and specialize in hip-hop, R&B, rock, and funk styles.

Podcast Transcript

Caroline: Welcome to Art Personals, a podcast made by Compound Yucca Valley, an art and event space in California’s high desert. Here, we ask some of our favorite artists to describe another artist’s work as best they can, with only their words and sounds. The one parameter is that the object they choose must be one they have seen in person at some point in their lives (whether that's an ancient artwork in the Metropolitan Museum of Art or a friend's painting in a garage).

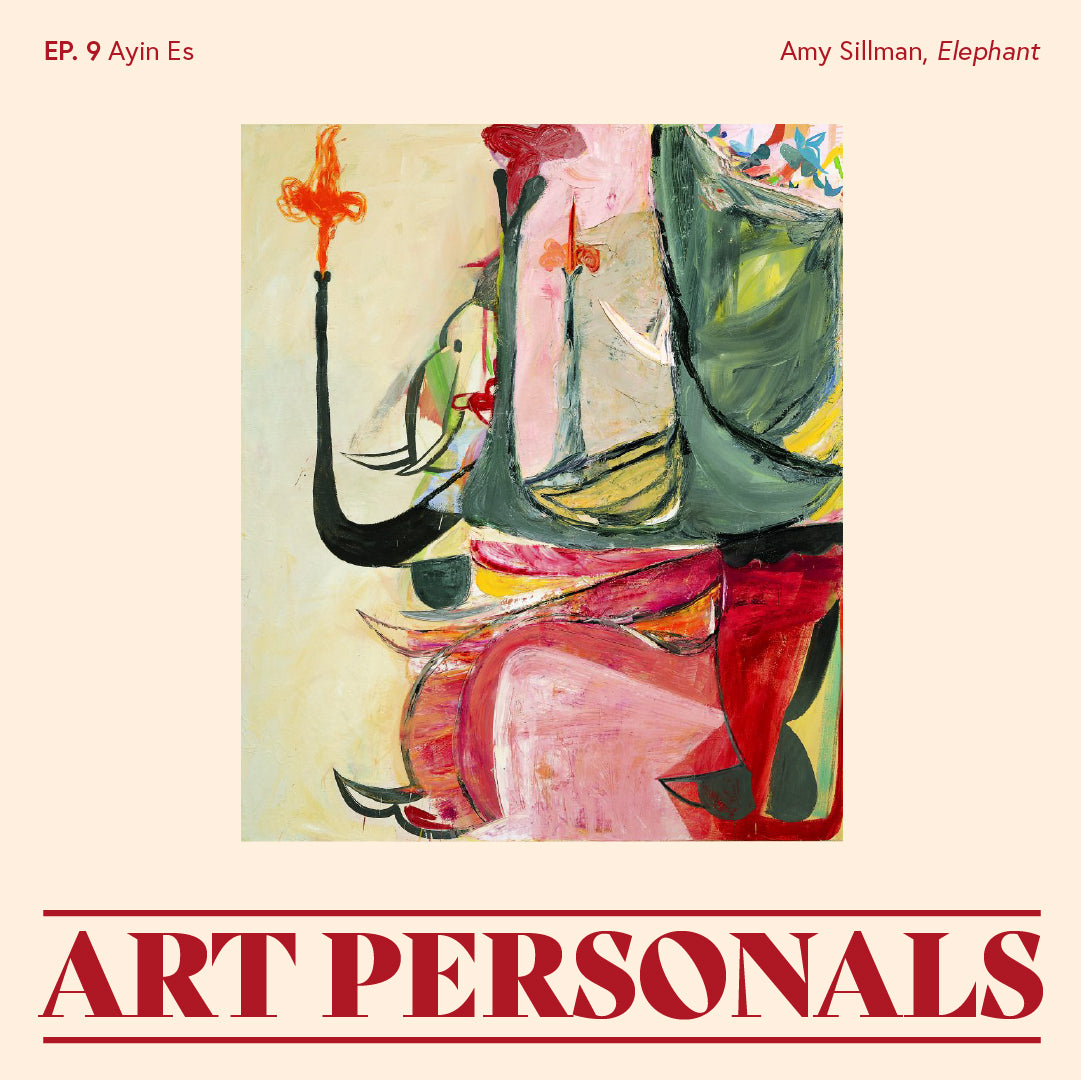

In this episode, we’ve invited Ayin Es to share their experience with Amy Sillman’s Elephant at Susanne Vielmetter gallery in 2005. Ayin is a multimedia artist, writer, and musician born in Santa Monica, and residing in Joshua Tree, CA, known for their unusual oil paintings, drawings, collages, and artist's books. Their solo exhibition, On the Mend, reflects their journey of healing from abuse, disability, top surgery and mental illness while navigating their identity as transqueer.

A two-time recipient of ARC Grants from the Durfee Foundation, they also won a Pollock-Krasner Fellowship, the Wynn Newhouse Award, the Bruce Geller Memorial Award from the American Jewish University, and an Artist Achievement Award from the National Arts & Disability Center at UCLA. Widely collected, their works reside in many predominant collections and museums such as the Getty, Brooklyn Museum, and National Museum of Women in the Arts.

—

Ayin: Amy Sillman is a New York-based artist, born in Detroit in 1955. She was raised in Chicago and moved to New York at 19. She did her undergrad at the School of Visual Arts and got her MFA at Bard. She works in many nontraditional media including drawing, installation, and animation. And she makes zines.

During the early 90s and 2000s, I made zines myself and collected them, too. Around then, I came across a funny little book of hers called Visiting Artist. It was about her being a guest resident at what I imagined to be the McDowell Colony in New Hampshire. I fell in love with her dark sense of humor and simple watercolor drawings.

Sillman's paintings are considered process-based. They move between abstraction and figuration. She has successfully married these two themes together. And around the time I was first aware of her, I was trying to do this very thing with my own work. I was trying to combine cartoons of my weird, dysfunctional family against abstract shapes I created from paper garment patterns, which were part of my early work background. Let's just say that some of these paintings were more successful than others. With narratives that weren't for everyone.

Sillman was randomly throwing in cartoonlike figures, or rather, body parts, like arms, hands, heads, feet, or whatever, into her compositions, incorporating them as simple shapes, which almost created narratives, but not quite. The paintings still read as legit non-representational abstracts. Up to this point I'd only seen her work online and in black and white print. Well, I saw a teeny weeny black and white image in The Art Scene which was a free gallery guide in LA at the time. She was opening one of her first solo shows at Susanne Vielmetter Projects called The Other One. This was 2005. I was excited to see this show. She'd been in the Whitney Biennial the year before, and the following year she'd go on to participate in the Triumph of Painting in London at the Saatchi Gallery.

I'd been an avid observer of abstract painting for a long time by then. I'm talking since I was six years old. It started with framed prints in the waiting rooms at doctor's offices. Psychiatrist's offices, to be specific, while I waited for my mom. There always seemed to be art on the walls in there, and I was endlessly taken with them. I had long periods of time to sit with the images. No one in my family had any connection to art, though I was just curiously moved by art, or textures, or brush strokes. I'd learned the names of the artists by the time I was a teenager, like Van Gogh, of course, Kandinsky, and Paul Klee, and all the abstractionists. I made a close study of them, like an obsession. I'm not a purist exactly, but to me, a true abstract outwardly represents nothing real. It doesn't fall into the decorative arts either, but since art is subjective, can you really differentiate what art is or isn't? Even experts can't do it. There are only countless, pompous academic views, a shitload of blurred lines, and naive opinions like mine.

You could probably tell I never went to art school, or even high school. I can't describe art with a formal philosophy or that transcendental idealism, whatever the hell that is. It's just instinct.

But anyway, on that day I went to see Sillman's show. It would be my first time seeing any of her paintings in person. And once I was in the gallery, I remember walking by the first two pieces, which may or may not have been a diptych. They were named Cliff One and Cliff Two. Both were on the larger size, like 72 by 60 inches, which was impressive. Art at that size has always screamed words to me like, this art is real and your art is rinky dink. But they were beautifully formative pieces that reminded me of scaffolding from a dream.

Then I moved on to one that was slightly larger and presented with a lot more wall space around it.

Amy Sillman, Elephant, 2005

And this was the one entitled Elephant. This painting just stopped me in my tracks. Feeling a little shocked, I stood there like a dope while something radiated in my throat. I had to swallow consciously. The feeling was visceral. This elephant painting was everything.

I can't just say it was a brilliant work of art before me. It had all the perfect surprises I didn't know I'd been wishing for, especially then. Yeah, it had some bright colors, but it still had a pretty limited color palette that made me deeply jealous. Yellow, gray, black, orange, and pink. There was a small scattering of reds and light blues and off-white. Limiting the color palette was something I had a real hard time with. I wondered if I could learn from this for once. I kept telling myself to pay attention, and something was lingering, an impression, a fantasy, like a half baked story that existed yet didn't exist at all. What? What am I saying? I mean, it had a sense of serious execution and absurdity at the same time.

A dream, and like something being in two places at once. Like how Jesus is everywhere at once, or something like that. I stared at this thing for a good 20 minutes before I started to get self-conscious about wearing my welcome out at the gallery. I always went gallery hopping on quiet days to be alone with the art in case of occasions exactly like these. What's funny, at first I didn't even look at the title card on the wall before recognizing the big elephant shape. Sillman simply titled it, Elephant. I didn't usually look for real things in abstract art. That's not my thing. But I feel like titles are important clues into what artists want or are asking from the viewer.

However, I only accepted that I was looking at an idea of an elephant. As I studied it, I wondered along the markings and how it was drawn. I pondered the movements and her decisions in every swing and curve of her brush. Certain featured areas erupted into pink and orange puffs of smoke while black and gray lines led me through a kind of circus scene. A road map straight into a big top where painterly white and blue flower chips spat out of an invisible chimney on the upper right hand side.

There was for sure a ridiculousness to it. When I was a kid I used to go to an amusement park in the far west San Fernando Valley of Valencia called Six Flags Magic Mountain with my friends and they had a suspension ride there called the Buccaneer. It was like a large pirate ship that fit at least 20 people on each side and it swung back and forth high into the air. I never went on that ride because I could tell it would have made me puke, but I'd watch my friends go back and forth, screaming the shit out of themselves while they felt the centrifugal forces pushing them into their seats and their stomachs inside-out. I couldn't help but think about that ride while staring at this painting.

Within some of the gestures I saw the outlines of crescent moons stuck on their backs. They were boat shaped, like shoes made for Aladdin. The elephant as a whole has these Arabian looking legs and feet, and it wears a party hat. Its tusk and trunk hang next to a black garment pocket of mystery, like a sardonic place to dip into when feeling a bout of darkness.

I mean, all of this may or may not be there in the painting, but that's what I see. Then again, I'm crazy, and it's probably not really there for anyone to see at all. Interpretations are meaningless. These are all just visual suggestions and lines drawn in paint. It all starts with the line after all, that magic line that flows from the mind to the hand into the pencil and across the blank page.

That's when it hit me that Sillman knows how to utterly transpose raw imagination, which was a skill I'd been chasing after using only my intuition. But she has some formula that makes it look effortless, with a swish-swish over those scraped off layers of a well worked canvas. Adding, taking away, blending, scratching, marking with bold color or no color at all. Elephant has both big and small thoughts, ideas made with knives and brushes that speak a special, sublimated language. Sillman is not speaking in pictures or stories. This is the voice of painting itself.

—

Outro: Thanks for listening to Art Personals, a podcast produced by Compound Yucca Valley. You have been listening to Ayin Es discuss their encounter with Elephant. If you enjoyed today’s episode, please consider supporting Ayin Es and their exhibition ‘On the Mend.’ You can learn more about CompoundYV and stay tuned for future episodes over at our website and our instagram @compoundyv.

Art Personals is produced by me, Caroline Partamian, Michael Townsend, and Lara Wilson, in collaboration with our artists.

Emiliano Vazquez mixed this episode.

Original music by Ethan Primason.

We curate shows for our virtual and physical spaces. If you are an artist interested in working with us, please send an email to hello@compoundyv.com.