Eric Nash Describes Jean-Michel Basquiat

Eric Nash is a California artist working in oil and charcoal. His subject matter focuses on icons and scenes inspired by Los Angeles and the California desert. His highly realistic images are pared down to their idealized essence often conveying a film still or a memory. He works in series, some of which go back decades.

Eric is a lifelong artist who began with community sponsored art classes at age 5. He went on to receive a BFA from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign on a talented student tuition waiver. He is represented by art galleries in Los Angeles and Palm Springs where he has had numerous solo shows over the years. His work is in collections internationally including well-known Hollywood names, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and corporations such as Delta Airlines.

He has been the subject of numerous media articles and his work has been collected or featured at The Hilbert Museum of California Art, Tucson Museum of Art, Laguna Art Museum, Riverside Art Museum and Palm Springs Art Museum. He currently lives and works in the high desert town of Yucca Valley, CA near Joshua Tree National Park.

The painting he describes in this episode is:

Jean Michel Basquiat (American, 1960–1988)

Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump

1982

Oil on canvas

96” x 164”

Art Institute of Chicago

Podcast Transcript:

Welcome to Art Personals, a podcast made by Compound Yucca Valley, an art and event space in California’s high desert. Here, we ask some of our favorite artists to describe another artist’s work as best they can, with only their words and sounds. The one parameter is that the object they choose must be one they have seen in person at some point in their lives (whether that's an ancient artwork in the Metropolitan Museum of Art or a friend's painting in a garage).

***

"Never out of all the things that I had seen, never had anything reached out and grabbed me like that and blown me away. The sophistication, the elegance, the chaos, the order, the meaning, the symbolism, the colors, the power, it was just something that I had never seen before and no one else had really up to that point."

***

That’s Eric Nash, speaking about his experience with Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump. Eric is a California artist working in oil and charcoal whose subject matter focuses on icons and scenes inspired by Los Angeles and the California desert. His highly realistic images are pared down to their idealized essence, often conveying a film still or a memory. He works in series, some of which go back decades. Currently based in Yucca Valley, California, Eric is represented by art galleries in Los Angeles and Palm Springs, and has been featured in exhibitions at the Hilbert Museum of California Art, Tucson Museum of Art, the Palm Springs Art Museum, and more.

***

I'm Eric Nash and I'm an artist, and I'm going to do a show at Compound in Yucca Valley this January.

I'm an old guy. Uh, I graduated from college in 1986. It was definitely a different time then. Um, we only got our information, uh, through really newstands, magazines, and then also bookstores, books where I would spend hours immersing myself in art, architecture, design, anything that I could find on this subject, which believe it or not, at that time there weren't very many books on much of anything. So you really had to search hard. Now, there were plenty of magazines coming out of New York, uh, that you could get where I grew up and where I went to school, which was the Midwest, downstate Illinois. But I was a very keen observer and I was hungry to see new stuff. I had grown up completely inundated with, uh, abstract expressionism and modernism. And let's just face it, it was the elite East Coast world of Yale and RISD and New York. And, uh, it was a rare place that you really weren't welcome unless you were part of that club. And you know, you needed to be clearly at that time, a white male.

This all seemed, uh, very stale to me. During the 1980s when I was in college, it just seemed kind of frozen and pathetic and, uh, I never really had much interest in joining that realm. So I really didn't know what I was gonna do, how I was gonna think as an artist. Now, the artist that I'm gonna talk about, I don't really have much in common with in terms of visual style or anything like that. In fact, I have very little in common with this artist, but in my long career of looking at art, over the years, going back to childhood, checking out library books and then, you know, all the way up until, uh, you know, graduated from college, I'd seen a lot and I had been able to go to the Art Institute of Chicago, which is an incredible museum because I lived a couple hours south of Chicago. And, uh, many of the other museums in Chicago. So I was pretty well versed. But again, it was a time when things were by the book and you had to be part of a certain kind of thought process, a certain kind of movement to be taken seriously and abstract expressionism was still there. Quite frankly, it was boring and it needed to change. In the early eighties in New York, lots of stuff was happening, and I'm sure any of you who are familiar with history know all the things that were going on in New York at that time, in the late seventies and early eighties. The punk movement, uh, graffiti, you know, hip-hop. It was just a hotbed of creativity that the world had never really seen before. It was so expressive, so real, so fresh and so new. And, it really changed the world. And I don't think people, you know, looking at it now, realize the depth and breadth of how much this has reframed, uh, the visual world.

The artist I'm gonna talk about, his name is Jean-Michel Basquiat. An American artist from Brooklyn, with Haitian roots. He had a phenomenal career and I'm sure that anybody who's listening to this knows who he is. He's basically a household name now, but there was a time when he was a very obscure artist.

Now in my intensive searches for, for new visual material, for trying to see what was going on as someone who was sort of stuck in the Midwest looking through magazines and books. One day, and I'll never forget this, I was in a bookstore and I don't remember whether it was a magazine or a book, but I opened it up and I saw the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

I couldn't believe it. I could not believe it. Never out of all the things that I had seen, never had anything reached out and grabbed me like that and blown me away. The sophistication, the elegance, the chaos, the order, the meaning, the symbolism, the colors, the power, it was just something that I had never seen before and no one else had really up to that point.

The intensity of his marks, the beauty, was really shocking at that time. He was not following any of the rules. He was completely carving a new path. And what's interesting about that time, it was still, uh, oh, let's call it the, the old traditions. Let's not even call it that. Let's call it what it was. Art was an elite world only. And if you weren't part of that club, you were outta luck. And especially for Jean-Michel Basquiat as a Black man, he was particularly outta luck. And, uh, the first things that you read about Jean-Michel Basquiat used language that probably wouldn't be used today. Words like "primitive." Jean-Michel Basquiat was seeking a raw language, something that was intense and of the moment, but by no means was it "primitive."

And a lot of the language that the art critics and writers at that time used, they always framed him as a Black artist. He was boxed, he was demeaned. He was not taken seriously. He did not have a degree. And, uh, anybody who I knew at that time and or even uh, knew him, dismissed him out of hand because he did not have that degree from you know, a legitimate art institution like, uh, Yale or RISD. Sorry to use those two as examples, but to me, they're part of the elite of the past that thankfully no longer has the, the same power that it, that it, uh, once did.

Now this world is open. Now this world is free. Now this world is connected. Now this world has opportunities for artists that we could have never have dreamed of back then. Jean-Michel Basquiat punched a big hole in that world and all the air came out of it. And there he was, uh, creating unbelievably magnificent, uh, pieces.

Iconic, uh, and, uh, Larry Gagosian was an early dealer of his and did a show in Los Angeles that is nothing short of spectacular. I, being a young man and not having much money, I, I didn't really have the opportunity to go see the work in person. I was much older by the time I got to see the work.

But through magazines and, and catalogues and other books, I, I became very familiar with his work with the nuances, the absolute power of it. Uh, I also spent a lot of time, you know, in any time I would have a discussion with an artist defending him. And really being, uh, an advocate for not only what his art was and how incredibly beautiful it was and how fresh and earth-shattering it was, but an advocate of, of him as, as a legitimate artist, which only came about maybe in the late nineties or or early 2000s, that he was really considered to be a legitimate artist because of this issue of him not having a degree.

Um, with that in mind, I think I completely reframed my whole way of looking at the art world, and I think that Basquiat made me understand that you don't have to be part of the system, that you can be outside of the system and recreate a new reality. And that's pretty much what he did.

Uh, you can say he was a hip-hop artist. You can say he was a graffiti artist. You can say a lot of things about him. But even during his earliest days when he was on the streets of New York, uh, he stood out and obviously people like, um, Andy Warhol wanted to attach themselves to his star, which they did. Many artists and art dealers who really understood it, wanted to be there with him and be part of him. But he was such a supernova that his work took on a life of his own, I guess you could say. And, uh, unfortunately we lost him at the young age of 27. And a lot of it has to do with, with fast living and drugs.

But in the time that he lived, he created an inordinate amount and an amazing amount of work and all of it, and completely channeled from the universe, something so big and so natural, and so raw and so real that none of us have ever seen anything like this before. Now, I know this all probably sounds ridiculous looking at it from today's perspective, but the earthquake that he created, completely changed the world.

Only later was I able to see his work in person, much later. Um, because a lot of it was really not in museums. Uh, it wasn't really taken seriously, but suddenly, you know, his reputation started to grow. People started to write legitimate articles about him. People started to understand who he was and what he meant, not only to uh, you know, the art community, but to America, American culture as a whole.

And he got his due. And I think one of the most triumphant moments was, uh, with the painting that I saw at the Art Institute of Chicago. Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump.

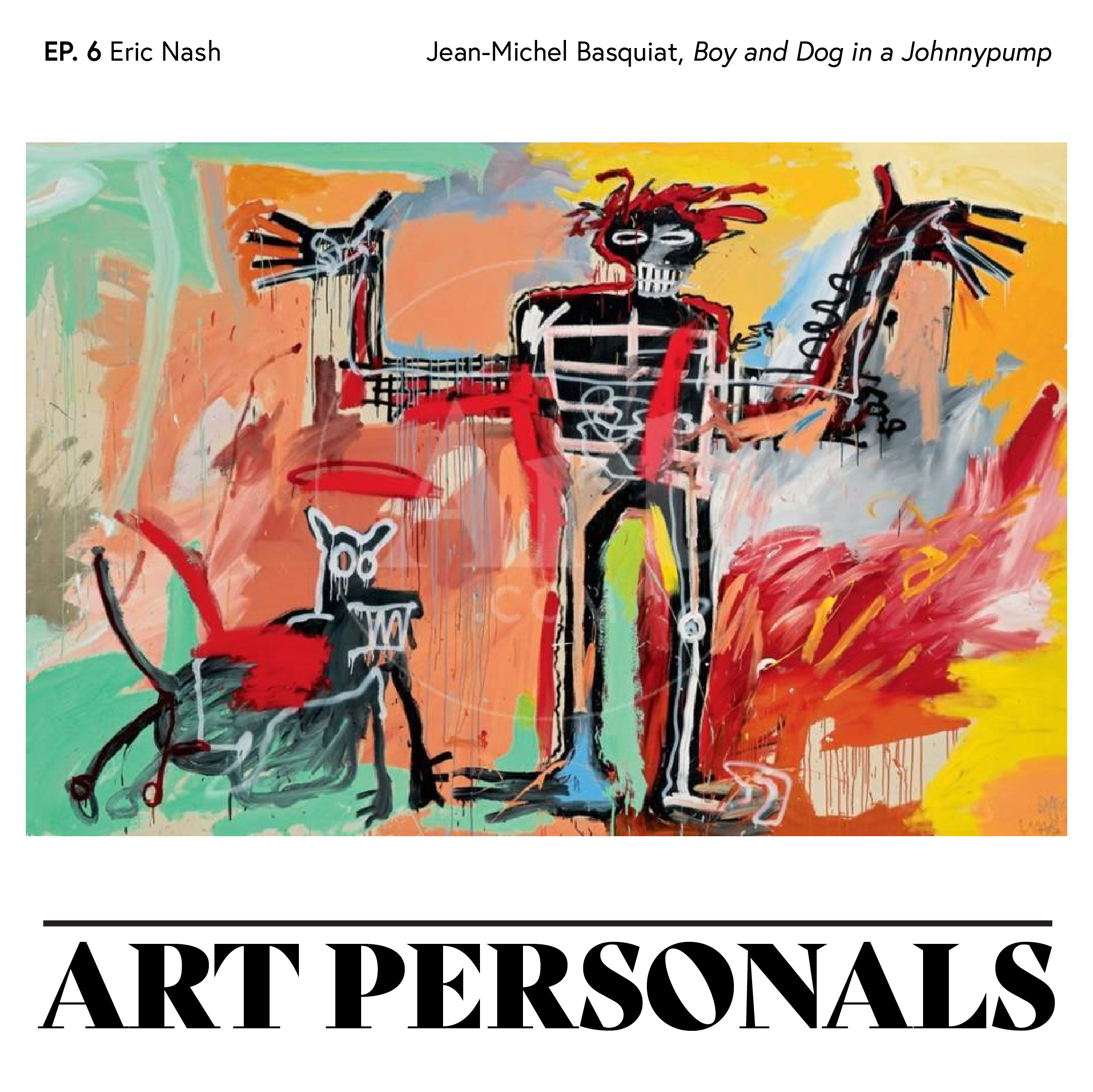

It was a mind-blowing, $100M piece that was bought and donated to the museum. Seeing it for the first time was an interesting experience only because, uh, you see how raw and simple it is, almost childlike in some ways. It's literally a skeletal figure, surrounded by glowing reds and oranges that are very exuberant and almost, uh, kind of unusual for Jean-Michel Basquiat. He used much more muted colors. In this case, it's much more vibrant, much more, more alive than much of his work.

Uh, it's spectacular in its singularity, I guess you could say. It's, uh, the, the, the character of the boy who is raising his hands, uh, whether that is, uh, raising his hands in, in triumph or in joy. And then to his left, there's a, there's a figure of a dog. And there's a sort of this chaos going on and this figure is emergent and joyful and triumphant within this chaos. And to me, it really is almost a portrait of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Uh, now, let me explain what a johnnypump is. I didn't really know this myself, but in New York, uh, they call a fire hydrant, a johnnypump. And what they do in the summer when it's really hot in a neighborhood, they'll turn on the, um, either the kids will, or, or maybe even the fire department comes and turns on the uh, fire hydrant, and it squirts water out in the all everybody runs and plays in that. So it's a joyous moment in any neighborhood, and he's captured that joy, but somehow he's also captured, um, immortality, man, nature, emotion and, so much power in this painting. It's huge and the fact that Ken Griffin, the billionaire, paid a hundred million dollars, for it and put it at one of the best museums in the United States, to me was validation of the reality, the value of his work.

Now, up, up until that point, obviously his work had gone at auction for very expensive prices. I love the fact that he went from very little and nothing to becoming what I would consider to be the most important American artist, maybe of all time. I mean, we don't have that long of a history, what is it, just short of 300 years, maybe the other artist would be Andy Warhol in terms of his cultural um, impact and his, uh, sophistication and understanding where things were going there's so much been written about Andy Warhol, but this, this is a whole new level. This is so great and so completely American that it defines us as us. His incredible, um, use of symbolism, references to, cultural ideas to racism, to cartoon characters, to sayings, to copyright, to, you know, his, uh, symbolic and seminal crown image. All of it is a vocabulary that could only be created by someone with his experiences, in 20th Century America. And, the amount of writing that he adds to his pieces. The amount of, uh, power that they have in terms of like, trying to figure out what he's saying, that you see hints and pieces, they're so completely engaging. Now, the, the painting I'm talking about doesn't really have any writing in it, and it's, and it's atypical to a lot of the, the stuff that he's done, but somehow it transcends. It transcends.

Jean-Michel Basquiat was well-known for, for using the skull, for using skeletons, for using, images that were, symbolic of a man without showing things other than, than the idea of a person, I should say, not necessarily a man, but the idea of a person. He would attach certain signifiers to show what kind of person that was. But often the idea that these were, these were souls, these were people without the specifics.

The impact I guess that this has made on me is, as I said, even though I'm not this kind of an artist, and I, I, I wish that I were, I wish that I were so consumed like this artist was: completely channeling something much bigger than himself and collecting from a lifetime of going to museums and all the things that he did, uh, to educate himself about art and about imagery, about whether that was European art, African art, going to the Brooklyn Museum when he was a kid, uh, looking at all the great museums in New York and knowing more in some ways than anybody who went to, uh, so-called, uh, art school and got a degree.

Jean-Michel Basquiat was a collector, a curator of thousands of pieces of vocabulary, whether that be words, whether that be visual images, symbols, and so forth.

One of the things that's always bothered me about art is the labeling of art. Whether this is a, a woman artist, this is a Black artist, this is a gay artist, this is a Hispanic artist. All these kinds of labels to me are, are meaningless. I mean, I know that they give context, I suppose, but to me, uh, the true nature of art should just speak for itself. The power that it has, the way that it reaches out and grabs you, the things that it says. That's art: without labels. And, uh, to me, so much of what Jean-Michel talks about, has to do with American culture, has to do with racism, has to do with perceptions of, of race and of status and ideas and things like that.

But, he brings all this stuff to the table in this, in this, what almost feels like a jumble, but it is more than that. It is, it is a, uh, a cornucopia of, of, of radical ideas of universal truths, realities and figurative movement and line and color that is just not repeatable by anybody.

Uh, and it was almost, as I said, the best way to describe him is a supernova. So seeing his painting slowly over time, one by one at museums and particularly, uh, the $100M painting at the Art Institute, it's been a pleasure to see these in person. And they're thought provoking. The wildness and the rawness of them is so different than so much of what you see in the museums, which is mannered, overthought and overwrought.

This is outside of that framework. Jean-Michel Basquiat colored outside of the lines and created a completely new way of integrating figurative imagery with elements of abstract expressionism and mixing and matching and creating a completely, uh, new style.

And, uh, you know, graffiti was very much a part of that. Uh, the, the freshness, the rawness of found objects, the simplicity of the materials, whether they be oil sticks, acrylic paint, uh, the quickness of, of the lines and the movement, all very inspired by graffiti, not held down by, uh, or not tainted by art school and hierarchy and what I would say, East Coast elite bullshit, which dominated the art world at that time. Um, what's great is so often with, as it was with Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, they met a welcome in California in Los Angeles. In fact, uh, Andy Warhol's, the first piece he ever sold was, was in Los Angeles.

Uh, I think there's something that worked with Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol about the West. There was a romance, there was a freedom, and there was a, uh, a place without labels and without restrictions and, uh, elite hierarchy in all the nonsense of the Euro-centric East Coast. None of that matters in California.

And to me the fact that Jean-Michel Basquiat did come to California and painted here and also, uh, spent time in Hawaii proves that he gravitated toward this place and toward the freedom that it embodies.

At that time, New York was the capital of the, of the art world and was the capital of the world, so to speak. That's obviously changing. Um, but he came to define the very best of what, what New York was at that time when it was a, uh, creative place when it was a, a dynamic place. Before corporations took it over, before it became an enclave of the elite and, and the wealthy only. This was a city that was very much alive and very much active and, and very real. And, uh, frankly, it was affordable. Artists could live there and out, out of that environment is, is where Jean-Michel Basquiat came. Out of the tension of New York, out of a city that was bankrupt in the late seventies. Out of the chaos on the streets, out of the opportunity and culture that existed there, out of the stark realities of racism. Uh, which really in some ways defines America. This black and white divide has been so much a part of who we are. And, uh, to see him topple the elite reality, was a joy for someone who was going back to the eighties when I was young, who, you know, I had a little bit of a punk attitude. Uh, it was a wonderful thing to see this happen because as I said at the beginning here, it was, it was a very limited world.

And this great artist created something so much more, for all of us. And I can only thank him for showing me what, what a real artist is. The kind of reality that he created is so far above myself or anyone that I know, that he was, uh, and again, I'll use this word, supernova. Uh, godlike, uh, a term that was used in, in the day about him was "The Radiant Child." That just speaks to his youth and his radiance as an artist is someone who literally these, these ideas, these words, these things, these objects, all these things were just coming out of his hands, just flowing.

And to me that that shows that there was some sort of higher purpose in him being here and in, in what he did. And he did not think, he just did. I know that, that's kind of an unfair way of looking at it. He thought immensely and deeply, but then he let go and it flowed out. So I have nothing more to say other than, we are indebted to this great artist and while labels are, are definitely part of his history and, uh, it, it goes so much, farther than, than labels and it, and it comes out in, in the truth and rawness of his drawings, of his paintings.

And, uh, that's it.

****

Thanks for listening to Art Personals, a podcast produced by Compound Yucca Valley. You have been listening to Eric Nash discuss his encounter with Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump. If you enjoyed today’s episode, please consider supporting this artist whose exhibition at Compound opens January 28, 2023.

You can learn more about Compound YV and stay tuned for future episodes over at our website and our instagram @compoundyv.

Art Personals is produced by Lara Wilson, Caroline Partamian, and Michael Townsend in collaboration with our artists. This episode was mixed and edited by me: gallery associate, Emiliano Vazquez. Original music by Ethan Primason.

We curate artwork for our virtual and physical spaces. If you are an artist interested in working with us, please send an email to hello@compoundyv.com.